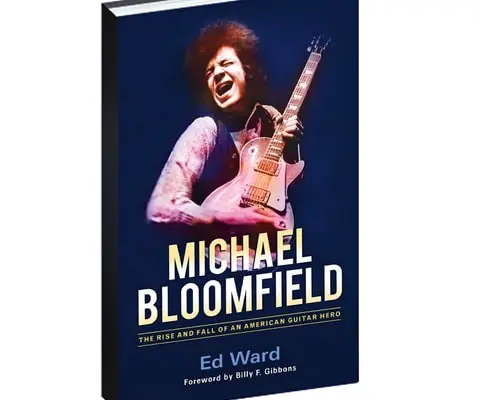

Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero

A book review by James Clarke.

“Chicago musicians played the blues and all the other cats were imitators.” Michael Bloomfield

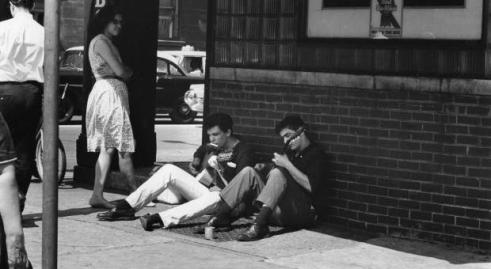

Bloomfield and his friend Roy Ruby playing at the corner of North and Wells in 1964. Photo by Raeburn Flerlage.

I remember the first time I heard the song “Born in Chicago”. The power of the sound coming from Paul Butterfield’s harmonica was like a freight train coming through the speakers—and then Mike Bloomfield’s guitar. That guitar. I played “Born in Chicago” over and over again until finally letting the whole record play through, flipped it, then on to side B. I spent the afternoon air guitaring “Our Love is Drifting” so intently that it made my fingers hurt.

In Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of An American Guitar Hero (Chicago Review Press), Ed Ward chronicles this magnificent talent and the conflicts he faced during a career that was anything but meteoric. He spent years learning from and playing with the best. Wanting to be the best. And most of all, wanting to create authentic music.

Bloomfield’s story is the stuff of legends: Chicago born North Shore kid kicked out of New Trier High School is accepted into the inner circles of the baddest bluesmen in the land only to be later challenged on his authenticity by critics and “historians.”

He fought insomnia. Many attribute his need to “turn it off” as a major factor in the drug use and addiction that took his life in 1981.

He wrestled with stardom: feeling the resentment of bandmate Elvin Bishop, an accomplished guitarist in his own right who’d been overshadowed with Bloomfield’s addition to the Butterfield Blues Band.

He wanted to be known for his talent and not for his name—rejecting projects and gaining notoriety for leaving gigs or not showing up in the first place.

He was wrought with anxiety: exiting in the middle of the night from the Super Sessions recordings with Al Kooper (Stephen Stills being added the next day in his absence). Legendary promoter Bill Graham, despite often being the victim of Bloomfield’s absenteeism, noted that Michael wasn’t as serious about anything in his life as he was his music and its authenticity.

Ward points to several examples of the critics getting to Bloomfield—not because of a performance or the quality of his work, but because they called authenticity into question. The first example was of Julius Lester who accused Butterfield Blues Band of stealing music that didn’t belong to them. Culturally. The second was a bad interaction with Alan Lomax—music historian and board member of the Newport Folk Festival who Bloomfield described as “introducing us in a scathing way-something to the effect that Newport had finally stooped so low as to bring this sort of act on stage.” These episodes left lasting impressions on Bloomfield, who, in response to Lester’s criticism, sought him out to confront him in person: “You know how many gigs I’ve played with black cats? You know how many cats have took me to be their protégés?” And to Lomax: “We brought an electric band and we played what to us was the music that was entirely indigenous to the neighborhood-to the city that we grew up in.”

Ward describes Bloomfield’s belief that Newport was a “scam”. That its board members reinvented the folk scene to fit in their image and that they even made the slick looking Lightnin’ Hopkins turn in his usual duds to look like a county boy for the sake of promotion. Bloomfield didn’t stop there. Later that weekend he would partake in what many believe to be a turning point in rock history: plugging in with Dylan and exacting revenge. Ward describes the volume of Bloomfield’s playing at that set as “a deliberate act of provocation” that was remembered by one audience member as being “obvious Bloomfield was out to kill.”

A great irony in all of this is that when it came to those directly involved in the music, Michael was authentic as it gets. Bob Weir has referred to Bloomfield as a scholar and a teacher to the west coast musicians. Muddy Waters introduced him frequently as his son. BB King wrote to him to ask him to come back to music after slipping out of the scene while on hard times. Bob Dylan, who invited Bloomfield to play on “Like a Rolling Stone” and with him at Newport in 1965—two defining moments in American music history—tried unsuccessfully to recruit him as part of his touring band. Bloomfield felt his place was with Butterfield—-playing Chicago Blues. Dylan would later call Michael Bloomfield the greatest guitar player he’d ever known.

Ed Ward does a great job of both referring to Bloomfield as a “hero” in his title while at the same time approaching his flaws without hesitation. We see a great character develop—part student; part star; part child; part old soul; someone pursuing perfection while riddled with imperfections.

A young man who aspired to be the real deal.

Be sure to “Like” us on Facebook!

Leave a comment