37 years later, a new book tries to set the record straight on Disco Demolition

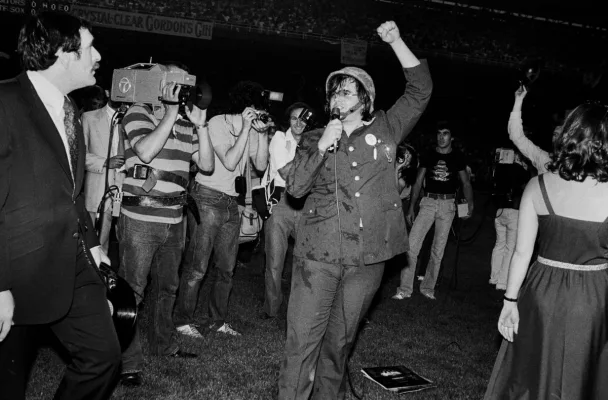

Photo by Paul Natkin.

On July 12, 1979, an event billed as “Teen Night” took place in between two games of a double-header at Comiskey Park, home of the Chicago White Sox. Mention “Teen Night” to another today, and it’s likely they won’t have a clue to what you’re referring to. But “Disco Demolition,” as it became known as, is recognized the world over for the events of that night which caused the cancellation of the second game of the double-header and arguably the death of the music genre that had taken the nation by storm.

A collaboration between radio station WLUP-FM and the Chicago White Sox, fans paid 98 cents [WLUP is 97.9 on the dial] to see the White Sox play the Detroit Tigers. The White Sox were 40-46, in fifth place in the American League’s Western Division. The Tigers were 41-44 in fifth place in the Eastern Division. As a baseball matchup, it wasn’t exactly a hot ticket. The White Sox averaged 18,000 people per game that year so if you look at attendance that night some say it was the most successful promotion in Major League Baseball history. While an exact number is unknown, some estimates say 70,000 people were at Comiskey that night, in a stadium with a capacity for 50,000.

By other metrics, the event was an unprecedented disaster. Fans began throwing records like Frisbees. One player, warming up before the first game, said he almost was killed by The Village People when a record flung from the upper deck stuck in the grass a few feet from where he was standing. Beer flowed (the legal age to buy beer was 19 in 1979) and other fans were likely smoking more than cigarettes. By the time WLUP personality Steve Dahl and his sidekick, Garry Meier, took to the field to blow up a large box of the collected records as Dahl led the crowd in chants of “Disco sucks!,” many of the fans were no doubt in an altered state of mind.

Dahl, dressed like a demented Army General, carrying a bullhorn and being driven in an Army-style jeep, whipped the crowd into a frenzy as full beers were being thrown. Once the records were blown up, fans stormed the field. They slid down the foul poles from the upper deck. They tore out seats and lit bonfires in the outfield. Police on horseback had to disperse the crowd. No one was hurt but several were arrested and the second game had to be forfeited because of the condition of the field.

Since that night, the legend has grown. Around Chicago, there are countless people who still who claim to have been there and likely weren’t closer than Clark and Addison Streets.

On July 12, the 37th Anniversary of Disco Demolition, Curbside Books will release Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died. Though local writer and radio host Dave Hoekstra wrote and compiled Disco Demolition, it’s credited to “Steve Dahl with Dave Hoekstra and Paul Natkin” (the latter of whom contributed the photographs) Dahl of course was the ringleader. Hoekstra attended Disco Demolition as a 24-year-old baseball and Rock and Roll fan, and Natkin photographed the event, mostly while riding on the hood of Dahl’s Jeep while holding onto a windshield wiper and dodging beers thrown by rowdy fans.

The book comes out now rather than on the events 40th Anniversary because Dahl wanted to address another angle that has emerged in the years since the event. Some have claimed that the event had undertones of racism and homophobia. While those opinions are expressed by Darlene Jackson and Joe Shanahan in the book, Hoekstra and Dahl say that it was a time of innocence without any political agenda other than to save rock music. That is up for debate, but one thing seems certain: Disco Demolition Night could have only happened in Chicago, and only on the South Side.

Bob Chiarito of the Chicago Ambassador recently talked to Dave Hoekstra about his book, the event and its effect on disco; and the allegations that there may have been more to it than defense of Rock and Roll.

CA) The first thing I was curious about is why now versus 2019 when it will be the 40th year anniversary?

HOEKSTRA) That’s a good question. They kinda came to me. Steve had been trying to tell the story and it turned out by happenstance all of were there. I know Paul Natkin was there. I was there and had written about it for the Chicago Sun-Times. Steve felt that it was time. I don’t think he wanted to wait for a round number anniversary. I think he felt it was time to clear the air. I think he was tired of defending himself about the homophobic and racist angle.

CA) He addresses that right away in the preface to the book. I don’t know if that was a criticism that came up back then or if it’s from people who weren’t there and didn’t live in that time.

HOEKSTRA) Second thing you said. I think it’s a criticism of people who were not there. It’s my book, I did the writing and I wanted to talk to as many characters as I could who were there. I was able to even track down the fireworks guy. It’s a time capsule of 1979. I think it was important to explain the cultural aspects of Bridgeport, what was going on in music and what was going on in Chicago radio. I pride myself on being a good reporter and a balanced reporter and if someone had brought up the homophobic and racism allegations I’d be all for it. Only one person really did, Joe Shanahan.

CA) DJ Lady D Darlene Jackson also mentioned it as well.

HOEKSTRA) Yes. I told the publisher, maybe that’s another book for another person. Talk to a bunch of younger people, 25 to 30 year-olds and have them look at it through the prism of today. Maybe that’s a book for somebody else. But I was there and it never entered the conversation. It was a bunch of people defending Rock and Roll. It wasn’t a big political statement. I know people will bring that up and I’ve never been afraid to tackle it. I don’t know how happy Steve was about me even putting Shanahan’s stuff in the book, but I told Steve that Shanahan is an important part of the book for two reasons. One, because he does bring that up and also from a music standpoint because he talks about how disco birthed House music.

CA) What will people get out of the book versus the documentary that was made on the 25th anniversary?

HOEKSTRA) I think it goes deeper. I think Mike Veeck [son of White Sox owner Bill Veeck who had the idea to stage the event at Comiskey Park] hasn’t been involved in a lot of the projects. I spent two years on the book, I can say Mike Veeck is one of the most poignant parts of the book. I’ve told people, Steve’s career ascended after it, but Mike’s career fell apart. I know that Mike wanted to have a career in baseball and was very daunted by the shadow of his father. Every good story has a lot of conflict and drama and Mike Veeck brings that. He said in the book, ‘The only people who wanted to hire me were soccer people because they like riots.’ And of course you have the angle of his father taking the blame for him. I think it’s really powerful stuff. I knew it had to be a bigger book than just Steve Dahl so that’s why I talked to so many people.

CA) To get back to Mike Veeck, why do you think he was blackballed from Major League Baseball after the event?

HOEKSTRA) First of all, his father wasn’t well liked within baseball. His father and Charlie Finley [owner of the Oakland Athletics] were outcasts. So that was one strike against him. It was a crazy event.

CA) Was there anyone that you couldn’t get that you wanted?

HOEKSTRA) Off the top of my head, I tried to get Giorgio Miroder, since Donna Summer is no longer around. There’s also a funny sidebar story — there’s a guy named Rusty Torres, who was an outfielder who played in nickel beer night in Cleveland, Disco Demolition Night, and the last game of the Washington Senators, [all three of which resulted in forfeits.] I wanted to get him, but he’s in jail.

CA) What would you say surprised you the most during all your interviews for the book?

HOEKSTRA) Everybody looked at it with a sense of humor except for “The Sodfather” Roger Bossard, [head groundskeeper for the White Sox]. He was very stern and interesting. He was like, ‘You think this is funny? How would you like it if somebody came into your house and knocked over all your furniture?’ That was one of my memorable interviews. He was the only one who was really bummed out about it. Everyone else enjoyed talking about it. It was almost like when they talked about it that it was a time of innocence. Obviously nothing like that will ever happen again.

CA) Reading the book I took a couple things out of it. One, that it would never happen at Wrigley Field; and two, if the White Sox were a better team that year it may not have happened at Comiskey Park either. But, it just seemed like such a South Side thing. Can you talk about that a bit?

HOEKSTRA) I’m glad you got that, because that’s an important point. When I write a story or do a radio show, I assume people know nothing about the subject. I think it’s important for people to know what Bridgeport is about. My dad worked in the Stockyards. I’m a Cub fan but my first game was a Sox game in 1965 against the Yankees when Mickey Mantle was on his last legs. I saw a little bit of what that team meant to the neighborhood then and you know the story, jobs left and things changed. But I really tried to find people who could speak about the neighborhood. That’s why I’m glad I got Jack Schaller [recently deceased owner of Schaller’s Pump in Bridgeport]. Another one I think about is chef Kevin Hickey, who has great stories in the book about walking to the ballpark and knowing everybody. He also brings up something that is really important and goes back to the homophobic/racist allegations. It was really about class. He talks about how he was a chubby kid and really related to Steve on a class level. I listened to Steve at the time and his whole thing about Rod Stewart’s “Do You Think I’m Sexy” was about the dress and standing in line to get into places. And Kevin as a kid was chubby, he was kind of a slob and really related to that. I think that speaks to what Steve was doing on the air. He wasn’t doing any race-baiting or homophobic stuff. I’m not friends with Steve really but that kind of bothers me to hear, especially from people who were not there.

CA) It kind of seems like revisionist history.

HOEKSTRA) Yeah, that’s it. I’m not afraid to tackle that issue if it had come up more but it really didn’t come up much at all. And the sample size of the people I interviewed were mostly people who were there. It was really about class and that’s the Bridgeport thing. It’s still that way today if you look at the Cubs-Sox rivalry, it’s really about class.

CA) The book also makes the case that Disco Demolition spelled the end for the band Chic. How much did it effect disco groups or was it coincidental timing, that disco was going away anyway?

HOEKSTRA) Yeah, that’s true. I think if I had more space and more time I’d go more into that. What is disco though? Nile Rodgers talked about this a bit in the book. Disco evolved and morphed. I think this event accelerated the change. They even received national and international attention. Nile claimed that they couldn’t find work after it. But all good music evolves. There’s House, there’s EDM. I shouldn’t say this, but Disco really didn’t die to me. To me, Madonna is disco. I listen to some, I listen to The Ohio Players. I don’t like the Bee Gees that much. I just didn’t like what was happening in Rock and Roll at the time.

CA) That’s the other thing. There’s a lot of bad rock music.

HOEKSTRA) I did a sidebar with the top 10 rock songs of 1979 and The Knack had the top spot.

CA) My Sharona, that was pretty bad. Now I know the White Sox averaged about 18,000 fans in 1979 and had a capacity for close to 50,000. Now they say 70,000 were at Disco Demolition. What do you think?

HOEKSTRA) I don’t know. After the people rushed the field we left. I was there to see a double-header. There was no pushing and shoving to get out, we just walked out.

CA) Nobody got hurt, right?

HOEKSTRA) No, nobody got hurt. I don’t remember the Dan Ryan being backed up with people on foot [as legend has it]. There may have been people trying to get into the park, but there were not people on the Dan Ryan. I looked it up and the reported attendance was 46,000. Maybe 50,000 to 70,000 were there but I don’t know. It was 98 cents to get in if you had a record. One problem is that they had ticket booths that were like phone booths that stood alone and they didn’t have enough of them so people just started storming in.

CA) How did you vet the people who claimed to be there?

HOEKSTRA) Some I knew were there. I got John Prine’s niece [Anne Sorkin] whose story was so detailed and wasn’t full of hyperbole. Some people I talked to I didn’t use because I wasn’t sure. I didn’t get too heavy on the fan angle because of that very reason. Too many people say they were there and weren’t.

I wanted to get [Don] Kessinger who was the manager then but I heard, and I haven’t confirmed this, that he has Alzheimer’s now. I really wanted Thad Bosley who I did get because he played on both sides of town and is a musician. I really wanted to get the baseball guys because I don’t think many other accounts had much of them.

CA) There really hasn’t been anything like it since, probably because it’s so much money to go to sporting events now.

HOEKSTRA) Yeah and I think the Sox should embrace it. I don’t think they should shy away from it. It really was one of the last periods of innocence in big league sports.

Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died will be released July 12.

Be sure to “Like” us on Facebook!

Leave a comment