Two films from two Chicagoans shine the light on Nelson Algren

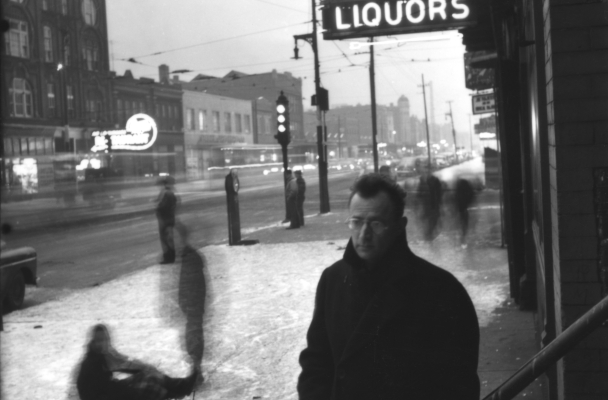

Nelson Algren. Photo by Art Shay.

Nelson Algren has been dead for nearly 35 years and since then has been nearly forgotten by mainstream readers, despite being considered by some as one of the finest American writers to ever publish. Famous for writing about the underclass, Algren is best known for his books “The Man With The Golden Arm” (which won the first National Book Award for fiction in 1950), “Chicago: City on the Make,” and “A Walk on the Wild Side.”

Two new films — one which just premiered last week and the other which has a premiere in the works — are reintroducing Algren to the world. Both are different films, but share the love of Algren. Both directors spoke to The Chicago Ambassador.

Interviewed by Bob Chiarito for The Chicago Ambassador.

Native Chicagoan and Columbia College professor Michael Caplan directed “Algren“, which premiered at the Chicago International Film Festival last week.

CA) Why this film now?

Caplan) I think it’s just as good of a time as any when you’re dealing with someone who is historic. The reality is, I met Art Shay in 2008 and we started it in 2009 and this is how long it took. There was no great planning in that regard. I do think that there is never a bad time to discuss these kind of issues. I think you can make an argument that there’s as much need to pay attention to people at the bottom of the social structure as ever. It’s not like it’s all gotten better and gotten fixed.

CA) How did you happen to meet Art Shay? (Professional photographer Art Shay, now 92, was a personal friend of Algren’s and took hundreds of photos of him over the course of several years, many of which are featured in “Algren.”)

Caplan) It was totally happenstance. I was at a photo gallery opening and a mutual friend introduced us. We just got to talking and we hit it off.

CA) You complimented him about his Algren photos and he proposed making a documentary about it, correct?

Caplan) That’s it, that was it.

CA) Were you surprised that no one had made a film about Algren?

Caplan) I was very surprised. The more I looked into it, I saw that there had been at least two or three examples of projects that started but that weren’t completed. There are always projects that get started and aren’t completed. I don’t think it was anything specific about Algren. It’s hard to get films started and get them finished.

CA) How did you raise the money for your film? Did you do any crowdsourcing?

Caplan) It was a combination of things. We did some Kickstarter stuff that didn’t succeed at the time but we got a lot of money from the same people who pledged the Kickstarter through Paypal. It was a combination of individuals, some of our own money and grants.

CA) You grew up on the Southeast Side of Chicago, correct?

Caplan) Yes, 102nd and Yates Ave.

CA) Where you always a fan of Algren?

Caplan) I really didn’t discover him until I was in my early 20s. For me, when I read his books I immediately identified the Chicago that he wrote about. Also, it was a shocking picture of the things that we don’t normally see.

CA) Did the film take longer to finish than originally thought?

Caplan) It always does. I’ve made three feature-length documentaries and they’ve all taken five years and I always think it will take less.

CA) What would you say is the main goal of your film?

Caplan) First and foremost, it’s to bring Algren into the canon of twentieth century literature where he deserves to be. There are other goals — to bring up to people the things that he advertised such as paying attention to the world around us and as soon as we put somebody in that ‘other’ category and say they’re not one of us, we are cutting off a part of our society. I think also he wasn’t a ‘complete artist’ in that in didn’t just go and visit places, he lived there. His whole thing was very holistic.

CA) I don’t know if he can be described as Gonzo, but he participated. More than some someone like Mike Royko and some of the reporters, or Studs Terkel –

Caplan) That’s right. There’s a brief mention in the documentary, the Gonzo journalists felt like they owed him something. They wrote from where they were and that’s what he (Algren) did.

CA) You had a lot of well-known people involved in the film. What was it like working with Wayne Kramer (of the MC5 fame) on the score?

Caplan) That was amazing. I never would have thought that something like that would happen. It came out of the fact that we got to know him by interviewing him for a film because he had written a song about Nelson Algren (Nelson Algren Stopped By). Then it was a matter of working on the actual score, and it was great. He could work in every music form — rock, jazz to more classical. He really had a wide range and I was thrilled.

CA) How did you find out that Billy Corgan (who is interviewed in the film) is such a big fan of Algren’s?

Caplan) Again, another happy accident. He is a friend of Art Shay’s. He brought it up to Art that he had strong feelings about Algren and that if we wanted to interview him, he’d be available.

CA) What surprised you the most about Algren?

Caplan) His sense of humor. His work was so dark that you might think he was a dark guy, but he really wasn’t dark at all. He had a great sense of humor.

CA) He did fall of the radar for some time. Why do you think that happened?

Caplan) I think it was a combination of things. I think he didn’t really try to create an image for himself in the way that Norman Mailer or Earnest Hemingway did. Or Hunter S. Thompson. He didn’t try to do that. I think it was also that he didn’t want to court the East Coast elite. It’s kinda like the old Groucho Marx saying: ‘I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.’

CA) Watching the film, I kept thinking about all these photographs that Art Shay took of him over the course of years — Nelson had to have been aware or been a sort of ham, knowing that something would happen with the photos one day. Would you say he was a little bit conscious of his image by having Art Shay tag along and take photos of his everyday life?

Caplan) I think that’s a great question. That’s a hard thing to answer because all we have at this point is Art Shay’s perspective on it. What I would say is that if you think of when most of those pictures were taken, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, there wasn’t quite the awareness of the media and the power of it. A lot of people feel like in politics the modern era didn’t start until 1960 with Kennedy who was on television and much better looking than Nixon. I don’t think there was quite an awareness of creating an image, but I think he had to have been somewhat aware of it.

CA) If Nelson was still around, what do you think he’d think of Chicago today?

Caplan) I think it’s more of the same. I think there are still areas that most people don’t want to look at and prefer not to pay attention to. I think he’d also say there are areas where everyone thinks everything is great. Look at Michigan Avenue, look at Millennium Park, it’s so beautiful, but the people in the poorer neighborhoods still get screwed, still get ignored.

CA) Is there anyone currently doing what he did?

Caplan) Yeah, definitely. I think Alex Kotlowitz is definitely doing it. I think if you look at TV shows like The Wire, — it doesn’t say these people are better or worse than us, it just says we have to pay attention to all sides of the spectrum.

CA) There’s another film about him coming out soon as well — have you seen it? Any thoughts on it?

Caplan) I have not seen it. I know it started in 1990 and was one of the three that I was aware of when we started.

CA) Was there any hesitation from you guys knowing that?

Caplan) Not really. We knew our approach. We had access to the Art Shay photos. No one had done it and we felt like we could go ahead. If we inspired these other guys to finish up after 24 years, I think that’s great.

CA) Algren is a complex character and there probably is room for more than one film-

Caplan) Right, there are thousands of biographies of Abraham Lincoln. I think there’s plenty of room for everybody.

CA) What was it like to premiere the film last week in Chicago?

Caplan) I can’t think of doing it in any other place. We had two sold-out shows and one matinee with more than 200 people. It was a great show of support. We hope this is the beginning of a long run of getting it out, with eventually DVDs and streaming also.

CA) What’s the plan now?

Caplan) The plan is to maximize visibility and you do that in the independent world by getting into festivals. We have three or four that look possible but I can’t say anything at this point. Usually you spend a year getting it to festivals and then see if you can do with a theatrical run, which for documentaries is really tough. I think we could do it in Chicago for sure.

Native Chicagoan Denis Mueller produced and directed “Nelson Algren: The End is Nothing, the Road is All“, set to premiere soon. Mueller, who now lives in Vermont, directed and produced the film with Ilko Davidov and Mark Blottner. Mueller also spoke to The Chicago Ambassador about his film.

CA) Why this film now?

Mueller) Well, Mark Blottner has been working on it since about 1990. He did several interviews during that period, but then he couldn’t do it for awhile. He called me up in 2012 and asked me if I’d be interested in finishing the Agren film. I said, ‘yeah, I think so.’ He sent me the interviews that he had done — I had helped shoot them– and when I saw them again, I knew it was interesting. It took us two years to finish the film.

CA) You live in Vermont, but you have Chicago roots?

Mueller) I’m from Diversey Avenue in the heart of the city. I moved away from Chicago in 2003 to get my Ph.D. at Bowling Green University. Then I taught documentary filmmaking in northern Kentucky for awhile and then moved to Vermont in 2011. I wasn’t teaching what I went to school for – my Ph.D is in American Studies, which comes out of English literature. And that’s why I love Nelson Algren.

CA) Where you always a fan of Algren?

Mueller) I first read him in about 1980 so I wouldn’t say always. I stumbled upon one of his books at the Strand bookstore in New York City. Of course I was familiar with him, but I hadn’t read anything. Then, when I did, I was like ‘oh, wow, this is really good.’

CA) Do you have a goal for the film?

Mueller) We’re trying to get it out there to the public like any filmmaker. Our goal is to make a good film, to get it out there and tell the story. Also, the story also about how Nelson was tapped by the FBI…they had a 1,000 pages on him, it was enormous. You asked me ‘why now?’ — that’s a very good question. That’s part of the reason, because we’re in the age of surveillance so a lot of the things Algren was writing about – the political Algren especially, which is a huge part of who he was — it’s as valid today as when he wrote it a half century ago.

CA) That’s a large part of the film?

Mueller) That’s a part of it. The film is the story of Nelson Algren. A man who was very talented but not an angel. He was a very tarnished angel. As I said before, sometimes the FBI got Nelson, and sometimes Nelson got Nelson. We also wanted to talk about how in the United States, we don’t treat our artists very well here.

CA) During the filmmaking, what surprised you the most about Algren?

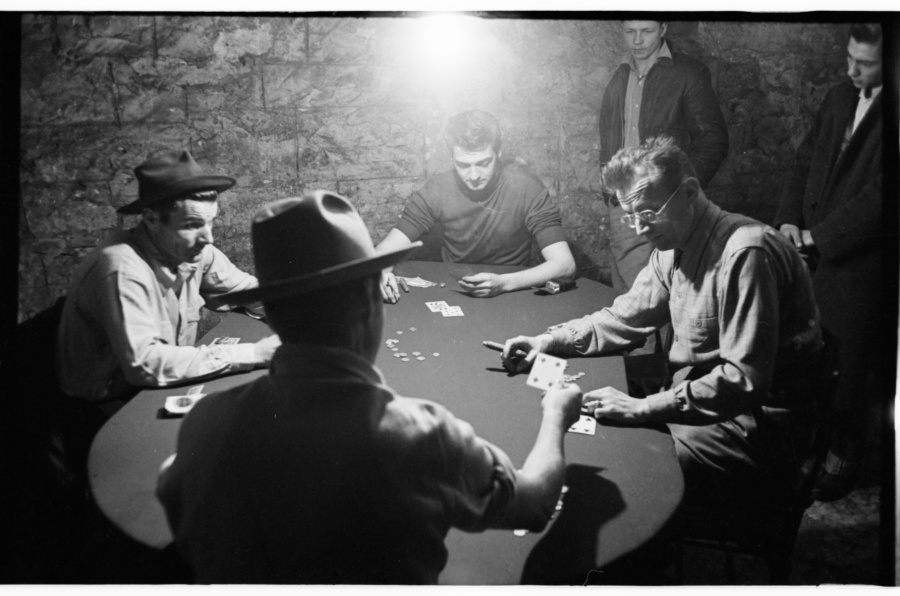

Mueller) How dysfunctional he was. We’re all flawed, I’m mutually flawed. Kurt Vonnegut said something in our film about the pathological nature of his chronic gambling. It makes a good story though, because what do you look for? You look for a clearly interesting character. He wasn’t one dimensional, he was complicated. And that makes a good film. He was a perfect character. I ended up really admiring him, I wish I would have known him, we could have talked about the White Sox.

CA) What do you think Nelson would think of Chicago today, or society today in general?

Mueller) I think he’d find a lot of the same things. I think he’d be horrified about the media, the shelling of America. He talked about that, how Americans are fearful. I don’t think he’d be particularly surprised. He wrote about the underclass so he’d be writing more about blacks if he was around today. I don’t think he’d have a hard time, he was good friends with Richard Wright. I think he’d still be writing about the underclass but they’d be more black.

CA) Why do you think Nelson Algren kind of fell of the radar for so long?

Mueller) First of all, I think the FBI marginalized him. The hard thing about the blacklist is that you didn’t know you were being watched. You didn’t know they were intervening on your career. So, with the cancellation of his book contract at Doubleday, I think he kind of stepped aside for a bit. And you know, the times changed. The world was changing fast.

CA) There’s another film about him that just premiered — have you seen it? Any thoughts on it?

Mueller) No, I haven’t. It’s a unique situation. The films have nothing to do with each other. All of a sudden there’s two films about a somewhat obscure writer who died in 1980, now almost thirty-five years later. Maybe it’s a testament to the complexity of Nelson Algren. I haven’t seen the other film so I can’t really comment on it.

CA) Any idea of when and where “Nelson Algren: The End is Nothing, the Road is All” will premiere?

Mueller) We are working on getting into several festivals right now and hope to show it in Chicago in March.

3 Responses to “Two films from two Chicagoans shine the light on Nelson Algren”

[…] a big part of Michael Caplan’s documentary “Algren” that recently premiered. In our recent interview with Michael, he said that he met you through a mutual friend and that you suggested making a film on Nelson to […]

[…] Yeah. I consider myself a Chicago filmmaker. If you look at someone like Nelson Algren, his writing is true Chicago stories. It’s not about Michigan Avenue. Like Alex Kotlowitz, […]

[…] Last year, two documentaries about Algren were released. I interviewed both directors which is a big part of why I wanted to talk to you today. I’m sure you were aware of those […]